Nvidia’s GTC conference is over, but if you want to see what’s coming with AI, including generative AI like ChatGPT, robotics, autonomous electric cars, and the metaverse, watching the keynote by CEO Jensen Huang is worth it.

A great deal of Nvidia’s success comes from its work on the metaverse, which comes at a time when Facebook, which changed its name to Meta, has largely failed to bring a successful metaverse product to market.

Let’s explore why Nvidia’s metaverse effort has been wildly successful while Facebook’s became one of the most expensive failures in tech history. We’ll close with my Product of the Week, a Chromebook from HP that may be the best Chromebook ever built.

Nvidia’s Metaverse Success

Nvidia has been working on elements of the metaverse for about 28 years. It has focused on the commercial market almost exclusively because the business sector would gain significant financial benefits from the metaverse. Not only is the commercial market more willing to pay for an expensive tool, but the resulting potential savings would also significantly mitigate the initially high price of any new technology.

After all, PCs were corporate tools at volume, to begin with. Due to their high cost initially, the consumer market for PCs didn’t emerge until much later. Microsoft did something similar with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the HoloLens, allowing it to outperform peers like Google Glass significantly at the start.

Nvidia — whose metaverse tool is called Omniverse — also realized early on that it couldn’t create its metaverse tool alone, so it partnered with many companies to develop both specialized workstations and servers and the necessary critical services needed to deploy the result.

Whenever Nvidia talks about its Omniverse success, the conversation includes massive numbers of partners who were, are, and will be needed to ensure a positive outcome for an offering that has to integrate highly with the real world.

Mainly through its GTC events, Nvidia drove interest and training into the segment. Over time, it has created a comprehensive set of tools that help developers create their own metaverse instances and populate them with content. About that content, Nvidia has driven a universal design language so that virtual objects can be made at high speeds to complete Nvidia’s metaverse vision.

Facebook’s Metaverse Failure

Facebook didn’t really start to ramp into the metaverse until 2019, nearly 25 years after Nvidia began its effort. Facebook seemed to focus more on consumers than businesses with its approach. Consumers are very cost- and content-oriented. You can deploy a corporate tool with few uses, but consumers want value and breadth, and, unlike businesses, they can’t offset the cost of a product with cost savings, at least not in this area.

To succeed, Facebook would need to be more comprehensive in terms of content, cheaper in terms of price and related services, and better than Nvidia because tools used by consumers have a higher requirement for ease of use than professionals who are approaching technology as part of their job.

Facebook mostly tried to go it alone and incurred exorbitant costs connected to rapidly creating a metaverse, which appeared to tank Facebook’s valuation and eventually led to massive layoffs.

The company demonstrated that the cost of building a new market is just too great for any company to go alone, even one that was once as profitable as Facebook. You need partners, developers, and others to help carry the development cost because no one company has the resources or funding necessary to build an ecosystem, and the metaverse requires a deep ecosystem.

Since Facebook is funded mainly through advertising, it should be, but it isn’t a marketing expert. It doesn’t seem able to build demand for its products, which must be a big red flag for other advertisers because it implies Facebook isn’t good for marketing. It’s like a toolmaker who has never used the tools they make.

Not only did this lack of capability cripple efforts like Facebook’s metaverse, but it also hurt related efforts like the VR Headsets. Having what amounts to a marketing superpower but not understanding how or even when to use it would be uniquely stupid for Facebook if it weren’t for the fact that Google has the exact same problem.

While companies that don’t use their own technology are anything but new, they are generally unsuccessful, but even when executing poorly, these companies profit like crazy.

Wrapping Up

So, Nvidia was successful, and Facebook/Meta wasn’t. Nvidia worked on the effort for decades, built up a robust and deep partner system covering all aspects of the product, co-developed with customers that would use it, and used it themselves heavily during the development process. Thus, when Omniverse came out, it was a winner because the company rigorously developed a foundation for that success.

Facebook’s failure resulted from the company trying to move too quickly and alone. It never even seemed to try to get to a product offering that would be acceptable to its consumer audience, the costs associated with the development overwhelmed the company’s resources, and it seemed to lose track of its destination.

Launching a market isn’t quick or easy. It may seem that way in the end, but it often takes decades of work to ensure eventual success. Nvidia put in the time, effort, and ecosystem-building strategy, resulting in its metaverse success. Facebook missed that meeting, and even though it seemed to know better than most what needed to get done for a more consumer-oriented metaverse, it failed to execute.

Contrasting the two companies showcases the importance of long-term strategic planning, partners, and a clear idea of where you want to end up. It also shows that for technologies like the metaverse, the commercial market is a far better place to start than the consumer market.

HP Dragonfly Pro Chromebook

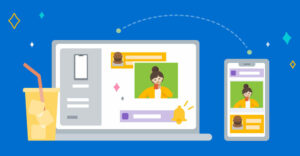

Last week I spoke of the HP Dragonfly Pro Windows Notebook, but today, I want to chat about its peer, the HP Dragonfly Pro Chromebook.

This Chromebook is arguably the successor to the old Google Pixelbook that didn’t sell that well but focused on providing a premium Chromebook for those who wanted more of an Apple-like experience but with ChromeOS, not macOS.

Created in close collaboration between Google and Intel, this Chromebook is a unique offering. It is an Intel Evo device which should mean fewer problems and higher reliability due to the extra quality control steps Evo promises.

The HP Dragonfly Pro Chromebook in Sparkling Black sports a 14″ touch display, 16 GB memory, and a 256 GB SSD. (Image Credit: HP)

On the outside, the Sparkling Black color Chromebook looks nearly identical to the Dragonfly Pro Windows product I covered last week. It has a similar finish, is constructed with a heavy focus on sustainability, plus:

- Long battery life;

- Decent performance — though the Windows AMD-based offering appears to have more power;

- A high-quality, backlit keyboard;

- Fingerprint recognition;

- 1,200-nit outdoor viewable display; and

- The same new high-performance charger that showed up in the Windows laptop. (Be aware that these chargers work poorly on airplanes, and you may want a three-prong extension cord for use on a plane.)

HP’s Dragonfly Pro Chromebook has more battery life and a far brighter display than its Windows peer but lacks facial recognition, which is common in most mid- to high-end Windows laptops.

This device is for those who really like the ChromeOS experience but are tired of the cheap hardware that tends to surround that platform. As a result, the HP Dragonfly Pro Chromebook, with a list price of $999.99, is my Product of the Week.