Social media fueled the bank run on the Silicon Valley Bank, a run that sent shock waves throughout the U.S. banking industry, according to a 53-page report released last week by a group of university professors.

In their study, the boffins used Twitter data to show that the failure of SVB was preceded by a large spike of public communication on Twitter by apparent depositors who used the forum to discuss the trouble the bank was facing and, more importantly, their intentions to withdraw their deposits from SVB.

The openness and speed of this coordination around a bank run are unprecedented, the researchers maintained.

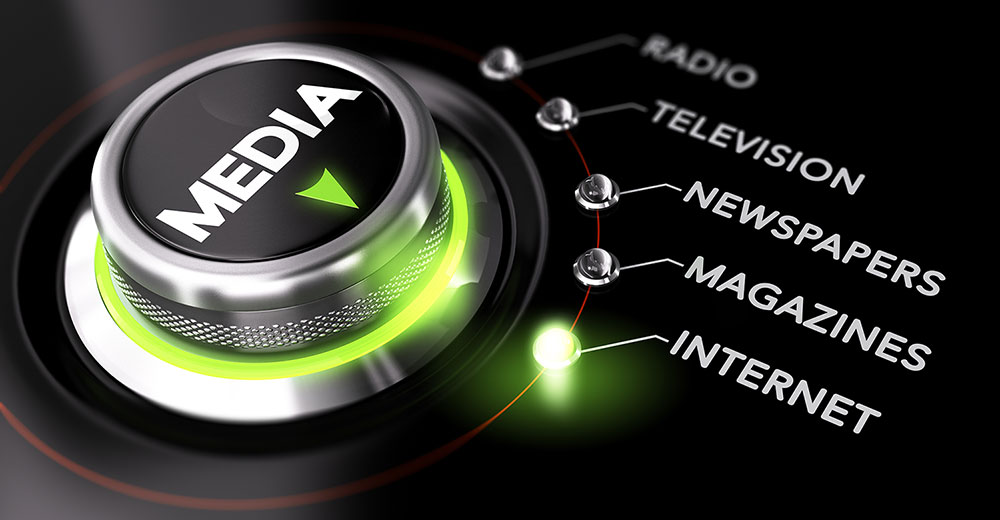

Mark T. Williams, a master lecturer in finance at the Questrom School of Business at Boston University, explained that bank runs before the advent of social media occurred as individuals communicated over much slower communications methods, such as mail, phone, or word of mouth.

“The effect influencer tweets had on the speed and size of the SVB bank run demonstrates the speed in which social media has accelerated the speed and the reach of communication,” he told TechNewsWorld.

“SVB failed because of bad risk management and a crypto contagion that spread across the industry,” he continued. “What Twitter did was speed up the process of the failure.”

“When influencers can touch so many people so quickly, that’s dangerous,” he said. “They can move the price of a stock or the value and stability of a company.”

“But Twitter didn’t cause the failure of SVB,” he added. “SVB caused it. Twitter accentuated it.”

Unique Risk Channel

The social-media-fueled run on SVB has serious implications for the banking industry, according to the researchers — J. Anthony Cookson of the University of Colorado-Boulder, Corbin Fox of James Madison University, Javier Gil-Bazo of Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Juan F. Imbet of Université Paris Dauphine and Christoph Schiller of Arizona State University,

The researchers noted that Silicon Valley Bank faced a novel channel of run risk unique to the social media era.

“SVB depositors active on social media played a central role in the bank run,” the researchers wrote. “These depositors were concentrated and highly networked through the venture capital industry and founder networks on Twitter, amplifying other bank run risks.”

More importantly, they continued, SVB is not the only bank to face this novel risk channel: Open communication by depositors via social media increased the bank run risk for other banks exposed to such discussions in social media.

“When information travels faster, people can run on a bank faster,” observed Will Duffield, a policy analyst with the Cato Institute, a Washington, D.C. think tank.

Trying to regulate that information, though, isn’t a good solution to the problem, he added.

“You want efficient markets. You want people to share information about the health of various firms,” he told TechNewsWorld. “I can’t see the First Amendment tolerating regulation.”

Social Media Gets a Pass

Social media platform operators aren’t in a position to address the problem, either, Duffield noted.

“I don’t think social media is in a place to be making these calls,” he said. “If you’re Twitter, you don’t know if a bank is solvent or not. You can’t look at their balance sheet.”

“You can suppress any claims of bank insolvency,” he continued, “but then you might end up preventing a lot of people from learning a bank is really insolvent, and they should have tried to take their money out of it.”

“When a rumor is going around, social media isn’t in a position to verify its veracity,” he added.

Cookson agreed. “There is not much that social media outlets can do,” he told TechNewsWorld.

“I don’t think of our paper as a call to action on the social media side because any restrictions on what users can post, or halts in communication, seem out of bounds, even if they’re connected to important real effects,” he explained.

“I don’t think it’s possible to regulate social media,” added Vincent Raynauld, an associate professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Emerson College in Boston.

“Any attempt to do so will be seen as an attack on a person’s right to express themselves,” he told TechNewsWorld.

Dangerous Groups

Mark N. Vena, president and principal analyst at SmartTech Research in San Jose, Calif., acknowledged that there are certainly market vulnerabilities that exist when social media posts run amok and cause bank runs or even push stocks higher or lower.

However, he maintained that since social media posts are a form of communication, he doubted that “general” posts can be regulated in a meaningful way to prevent these actions from happening.

“I could see barring company officials and individuals who own shares in a stock from making insider-related posts, but the current laws and regulations already manage that, and there are severe legal repercussions for individuals who disclose insider info,” he told TechNewsWorld.

“Where the danger for this really exists is if groups of individuals come together to create and promote posts that collectively have a stronger impact than if the individuals in the group made posts by themselves,” he said.

“If the information is purposely misleading to create a market distortion so someone could profit, there might be an opportunity to do some regulatory work around that,” he added.

Absence of White-Knuckling Banking

Cookson noted that even in the absence of action by bank regulators to curb the accelerant effects of social media on bank runs, there’s plenty banks can do to make their deposits less run prone.

“Our result is that social media amplifies existing bank run risks, like having a large percentage of uninsured deposits, so one important shift we might see is that banks will begin to manage their deposit risks more carefully since social media and digital banking make it riskier to rely upon uninsured deposits,” he said.

Duffield added that the Federal Reserve bailout processes could be improved. For example, he pointed out that there’s a 4 p.m. cut-off for transfers every day, even though business operates in a world of real-time, global electronic transfers.

“The lenders of last resort in our system need to take a good look at how they can move faster to keep up with the digital world,” he maintained. “These mechanisms may have worked fine in the 1970s and 1980s when everyone stopped doing business at 4 p.m., but everything moves much faster now.”

“That’s a big deficiency that’s been exposed by all of this,” he added. “There’s just a mismatch in speed between the withdrawal side and the bridge loan side.”

Another lesson learned from the SVB debacle is the difference between East Coast and West Coast banking cultures.

“The West Coast capital culture is young,” Duffield said. “A lot of what we saw with Silicon Valley Bank was the downside of that. There’s not as much long-standing developed trust. When it seemed like things were going bad, everyone ran for the exits instead of white-knuckling through it.”