Earthlings have a natural inclination to gaze at the heavenly bodies. Many even dream of reaching for the stars. Mae C. Jemison actually is planning to get humans to other solar systems within the next century.

Her goal is not an idle fancy. She has already been to space and back. Now her passion is to unite humanity to focus on traveling beyond our solar system.

On Sept. 12, 1992, Mae Jemison became the first African American woman in space. As a mission specialist on Space Shuttle Endeavour, she logged a total of 190 hours, 30 minutes and 23 seconds in space.

Jemison, who is also a physician, has worked as a Peace Corps volunteer and a professor. She is the founder, president and CEO of BioSentient Corp., a medical technology company, and founder of the nonprofit Dorothy Jemison Foundation for Excellence. It was through the foundation that Jemison made the winning bid for the DARPA 100 Year Starship project to further the goal of interstellar travel.

Jemison attended Stanford University on scholarship at the age of 16. She earned a bachelor of science degree in chemical engineering and a bachelor of arts in African and African-American studies. She earned a doctorate in medicine from Cornell University in 1981.

Following her career as an astronaut, Jemison left NASA in March 1993 to teach at Dartmouth College. She also founded the Jemison Group, which encourages a love of science in students and aims to spread advanced technology around the world.

Like other astronauts, Jemison found space travel was a profoundly life-altering experience. Seeing planet Earth from space changed her in ways she had not expected.

What stuck with her was the notion that beyond geopolitical borders we all are related as Earthlings. We all share the same sky. Human survival may depend on more people embracing that realization.

“We need to help people change their perspectives. It is not just about space. It is about how space exploration can help to make us better on this planet and as humans,” Jemison told TechNewsWorld.

Reaching for the Stars

In the years since Jemison left NASA, she has remained heavily involved in promoting spaceflight and space-related activities. She teamed up with Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) scientist Jill Tarter and Star Trek: The Next Generation actor LeVar Burton to create a new campaign called “Look Up.”

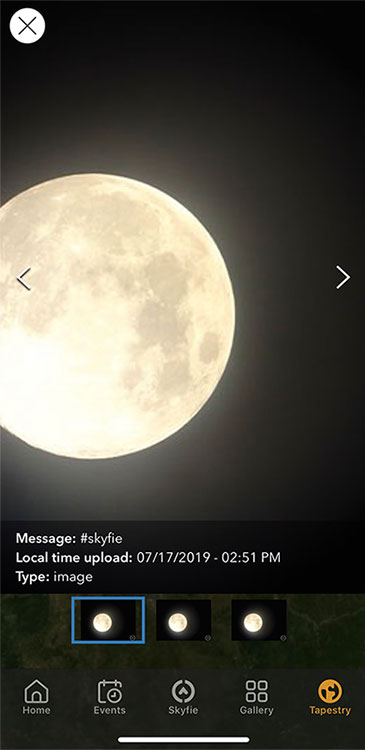

Look Up is a movement that encourages people to connect with the sky above us. Participants collaborate on weaving a global tapestry of Skyfies — sky selfies. The Skyfie app, available on Apple’s App Store and on Google Play, gives users an opportunity to capture their sky-looking images and personal feelings when they see the sky from a different perspective.

With this week’s fanfare surrounding the 50 Year Anniversary of the Apollo Lunar Landing, Look Up expanded to focus on “Look Up Apollo 11.” Skyfie app users’ images, audio and video, and text about the sky are displayed on the Sky Tapestry Globe.

People responded so positively to previous Look Up events that the world globe display had become heavily populated with contributions. Those displays were removed earlier this week to make room for Apollo 11 postings, Jemison said.

Many users’ image uploads are accompanied with reflections on their feelings, thoughts and hopes as they look up at the sky we all share. Participating by uploading from the app is not a mere public digital journal entry. It is a way to experience connectivity with other humans under the same shared sky.

Not All Star Gazing

The 100 Year Star Ship page on Facebook offers easy instructions: “Open your #Skyfie app, head to the photo-on-photo feature and snap a pic to show the world where you are in this moment.”

The Facebook page and periodic Look Up events are but two strategies for helping people to connect, react and think about the potential in the stars. Many channels of communication and a wide variety of events are needed to bring people together to interact, Jemison explained.

“It doesn’t always have to be events related to celestial stars. We have to get people to adapt to different platforms,” she said.

So far reactions on social media have been very positive. Now the organization is trying to find more ways to get people to relate.

Pushing for the 100 Year Starship Journey

The 100 Year Starship project is funded by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and National Aeronautics and Space Administration grant program. Its aim is to make human travel beyond our solar system a reality within the next 100 years.

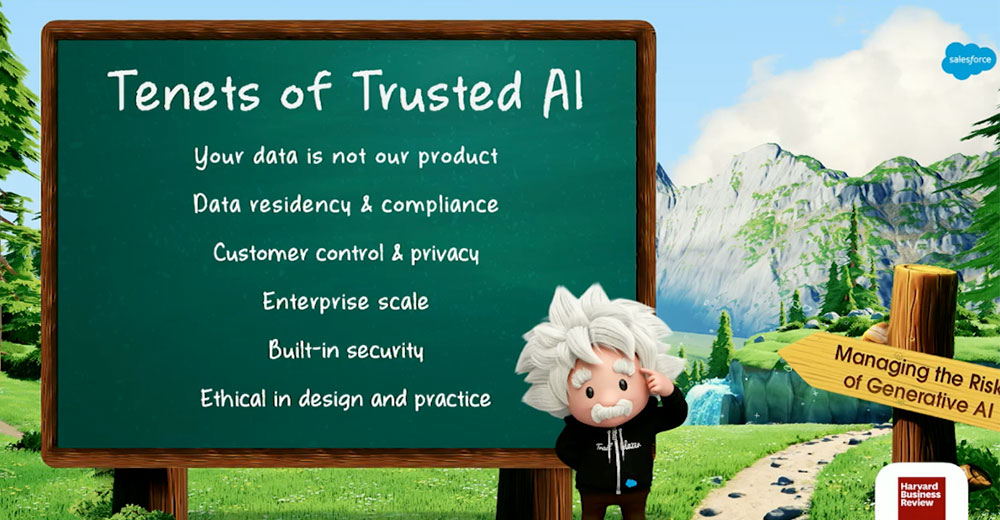

The logistical planning for preparing a foundation of research and businesses to support the journey is under way. Much of that preparation involves changing people’s minds about the value of space exploration.

The process involves building a grassroots understanding of what space travel means for humanity.

Jemison’s personal philosophy, as communicated in the 100 Year Starship grant proposal, is the idea of focusing on the inclusive journey, according to Look Up team member Jason Batt, creative and editorial director for 100 Year Starship.

“She has said over and over that space is not just for billionaires and rocket scientists. One of her other repeated comments is that ‘no one has to be shown the stars,'” Batt told TechNewsWorld. “It is something that occurs with each and every person in every society. Everyone looks up at the stars.”

Can’t Do It Alone

Going to another star system will not be achieved by one corporation or by one nation. It requires an awareness-lifting operation that results in people learning to see themselves as members of a shared humanity. People must recognize that we are not just a bunch of separate nations, Batt added.

“We are already space travelers on this Earth. That might sound corny, but the intent is to recognize what happened with Apollo 11 fifty years ago. We have to realize that as a nation we have got to have a common purpose,” he said.

Spawning the Inclusive Idea

At a panel event six years ago, Jemison was part of a conversation that planted the seed for Look Up. The discussion focused on the world filled with so much divisiveness.

“We all look up at the same sky. That spawned the idea of the 100 Year Starship,” said Batt.

That is one of the binding agents for Jemison and her staff. The next big leap in space travel will require a major lift for us as humanity at large, he said.

“We are not going to accomplish the next major step as singularly insular nations. I think that has been proven by looking at the international space station,” he said.

The ISS is the greatest space effort outside of Apollo, according to Batt. The participating nations made Earthlings space-inhabiting people.

“We crossed that threshold a few years ago. It is not a threshold that the U.S. could have accomplished alone. We had to have multiple nations,” he emphasized.

Inclusiveness and Beyond

Jemison sees a need for change in the next 50 years of space exploration. Everything has to do with how successfully organizers can involve people in participating.

“Who gets involved has to be people who haven’t just been involved with space all the time. We need people who are advocates,” said Jemison.

We need people with expertise in each subject area to make all of this work — that is a long-term commitment, she noted. One of the big tasks is to start talking about how to support ourselves away from Earth. For instance, we need to discuss virtual healing 10 years and 20 years out.

“We need to create a new medical infrastructure. Right now the medical infrastructure is dependent on what is here on Earth. It is a different perspective,” Jemison said.

Related hurdles are discussing what kind of disciplines can be jump-started and what kind of questions program leaders can ask, she suggested.

Changing the Story

People in the space business have not done a very good job of changing the story about how space exploration issues are connected, Jemison asserted. Change involves a process.

“It is a thought process. We are starting to see people becoming more connected. Part of the problem lies with building upon science literacy and a better STEM workforce,” she pointed out. “Our job has to be to show folks how pushing for these things makes us better.”

Perhaps the elephant in the space capsule is what about the moon and Mars? The bigger questions to be resolved touch on whether it first is necessary to go back to the moon and establish a base, or go to Mars and establish a base.

The answers have less to do with cost and technological challenges, according to Jemison, than with commitment — and with people understanding how we are all connected.