Can social media be saved? Can democracy be saved?

The first question may seem less compelling than the second, but to some very worried observers, they are intimately entwined.

Social networking — on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and a host of other online networks — is the root of all current cultural evils, in the eyes of some critics. However, campaigns to persuade users to withdraw from it have gained little traction.

Undeniably, social networks offer positive experiences that are hard to give up. They connect people instantly. They disseminate photos of newborn babies, delicious recipes and miraculously standing brooms. They let us know when celebrities — or old acquaintances — have passed on. They help raise money for good causes. They educate. They provide a forum for discussions that are penetrating and sincere. For some, they are an antidote for loneliness.

They also vacuum up users’ personal data and share it with marketers to support alarmingly targeted advertising campaigns. They provide convenient tools for bullies to harass their victims. They offer a platform for hate speech and terrorist recruitment. They distort the truth. They spread and amplify fake news and other lies. They sow distrust and enmity among family members and friends. They chip at the very foundation of long-treasured institutions. Some see them as an existential threat.

As part of a comprehensive virtual discussion on the state of technology in 2020, we put two central questions to ECT’s panel of industry insiders in an effort to tease apart some of these tangled issues. We asked them to identify the biggest problems with social media and to propose some potential solutions.

We also asked how concerned they were about the spread of disinformation online, particularly with respect to elections, and for their insights on how that issue should be addressed.

Our roundtable participants were Laura DiDio, principal at ITIC; Rob Enderle, principal analyst at the Enderle Group; Ed Moyle, partner at SecurityCurve; Denis Pombriant, managing principal at the Beagle Research Group; and Jonathan Terrasi, a tech journalist who focuses on computer security, encryption, open source, politics and current affairs.

Social Media Ills in a Nutshell

The trouble with social media platforms, according to our panelists, is that they make it so easy for people to behave badly. Also, people are too careless with their information. It’s too easy for an impulsive moment to go viral.

There’s a lack of foresight when it comes to managing these vast personal data respositories. Social networks have all but destroyed privacy.

Social networking is addictive.

Platforms are biased. Standards are not applied fairly.

They’re businesses that want to profit, above all else.

Some solutions? Break them up. Require licensing. Deploy artificial intelligence monitors. Regulate.

The Social Blob

Users are both the victims and the villains on social media, suggested Rob Enderle, who noted the tendency for people to post without thinking.

“In general, many people think they can hide behind the anonymity of their keyboards and use social media as a weapon to bully other people, with little thought for the consequences of what they type,” said Laura DiDio.

“Many people also overshare and provide too much information about themselves and their personal life. This too, can have unintended and often tragic consequences,” she added.

The social media business model is “exploitative,” remarked Jonathan Terrasi, “in the sense that consumers only nominally consent to it, very seldom providing truly informed consent.”

“Privacy is the biggest issue,” said Ed Moyle.

One “macabre factor” is that users’ social media accounts often outlive them, noted DiDio.

“I still get notifications for birthdays, anniversaries, etc., for deceased friends and coworkers,” she remarked.

The challenge of fixing social media may seem insurmountable, but there is no shortage of potential solutions on offer, ranging from creative ways to modify personal behavior to business self-regulation to accepting the need for governmental intervention.

“The most obvious solution is to practice discretion, but I’m not sure how realistic that is for many people,” said DiDio. “I’ve seen some people say they’re taking a break from Facebook or Twitter or Instagram in the morning only to be back posting a few hours later! To paraphrase Karl Marx: Social media is the opiate of the people.”

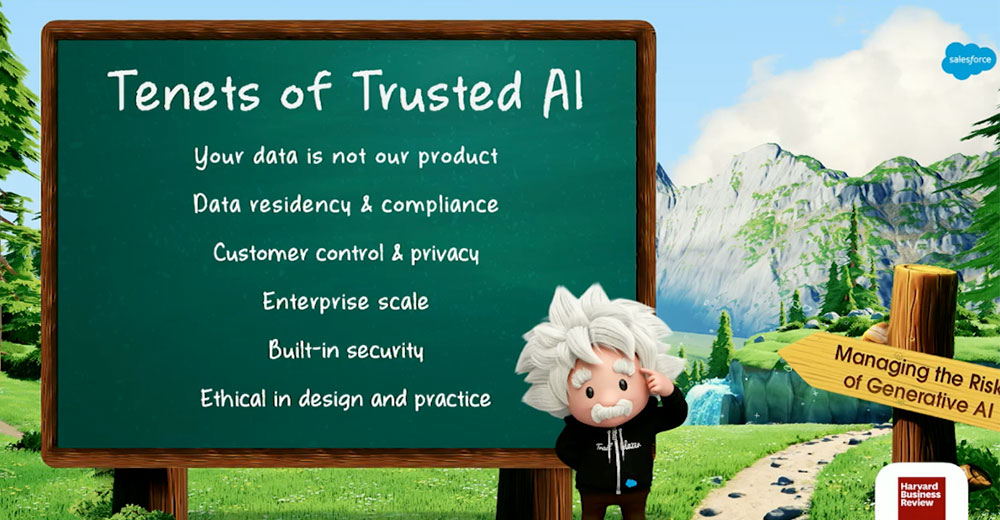

AI to the Rescue?

Instead of persuading people to stop using social media platforms, why not provide tools that can help them engage more wisely?

Perhaps artificial intelligence systems could be of use in this regard, Enderle suggested.

Imagine that you’re firing off an angry reply to your brother-in-law’s snarky political jibe and, as you type, a little thought balloon pops up and asks you if you really want to post that comment. Perhaps the AI even suggests language that makes your point in a less confrontational way.

Speaking Freely

“To me, the most significant issue with social media is uniform and transparent applications of a platform’s ‘community standards,'” said Terrasi.

“At this point, people seem to have not just conceded that social media puts limits on online speech, but have actually welcomed certain forms of what is, at the end of the day, censorship,” he pointed out.

“Whether it’s removing Islamic State (ISIS) content at the behest of the Obama administration, or social media cracking down on disinformation in the face of vociferous pressure from their users, policing certain kinds of speech on social media is a practice that users truly want,” Terrasi maintained.

“However, what we’re finding, both historically and presently, is that social media companies do not enforce their standards uniformly, and a lot of users — activists especially — feel that they are being dealt with more harshly than other users who have committed more grave infractions,” he said.

“It’s gotten to the point where different political factions believe that a given social media platform is secretly carrying water for their opponents, which at the very least creates a toxic atmosphere for discourse,” Terrasi observed.

“About 100 years ago, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote the defining standard for free speech,” said Denis Pombriant.

“It had something to do with issuing propaganda during wartime. Holmes said that the speech much present a clear and present danger to society for society to take action against it. That’s where we get the idea that free speech or not, you can’t yell ‘fire’ in a crowded theater. It makes sense,” he continued.

“Using that standard, there are many things happening on social media today that violate the standard set by Holmes. Rather than regulating speech per se, which is a never-ending pit to fall into, if we applied simple structures that have worked well for centuries already, we could reduce the problem to a minimum without trampling anyone’s rights,” Pombriant suggested.

The Self-Policing Approach

One of the underlying problems with social media is the internal corruption of the platforms that is attributable to runaway greed, suggested Pombriant.

“The CEOs represent a new gilded age,” he remarked.

“Social media has a business model problem that will be solved when they are broken up into platforms and apps,” Pombriant suggested.

Further, like other professional organizations that police themselves, social media platforms should be subjected to certification and licensing for professional participation, he argued.

“This works well for all kinds of occupations, from doctors and lawyers to electricians and barbers. You can cut your own hair, you can wire a socket in your own home, you can treat your own cold without professional intervention — but if you want to do any of those things for others you need a license,” Pombriant noted.

“Social media for personal use should not require any form of licensing, but when organizations use it to influence the public it is reasonable to require them to have demonstrated competency up to and including identifying who they are unambiguously,” he said.

“How many social media ills could be solved right now with just minimal transparency? Not having that transparency is the core of a clear and present danger,” maintained Pombriant.

“I see what you’re saying, Denis, and it seems very elegant on paper, but I don’t see that working in practice — at least in the realm of political speech, which produced the consternation that precipitated the present vigorous public discourse on online speech,” Terrasi responded.

“If corporate or governmental political actors identified themselves as such, then we could by all means require licensing on their part,” he agreed.

“The reality, though, is that nothing will compel these actors to do any such thing. If, for instance, a private sector entity with fringe political agendas wants to incept its narrative, they will just get people to create accounts and generate content under the pretense that they are individuals sharing their sincerely held personal beliefs,” Terrasi said.

“There is literally no way to police this practice, short of shaking down every user of every account and investigating the possibility that they represent some entity other than themselves,” he pointed out.

“Not only would these rogue political actors do this, but they have in fact done this: Russia sowed discord in the American public discourse in 2016 by fabricating fake personas of individuals with supposedly personally held beliefs, and these messages resonated with American voters enough that they were amplified,” Terrasi added. “I don’t see a realistic way to out every account that serves the interests of a larger entity, with or without licensing requirements.”

The Big Guns

Manipulation at a national scale requires “intelligent regulation,” according to Enderle.

That said, “I fear ‘intelligent regulation’ is an oxymoron,” he added.

“It seems to me that the only long-term viable solution is regulation,” Moyle agreed.

“Social media needs to make money to operate, and companies will derive revenue in whatever way they’re allowed, so the business model won’t change until substantive government regulation gives them an ultimatum,” Terrasi chimed in.

“I believe that eventually the liabilities surrounding social media will eliminate or nationalize most of it,” Enderle predicted. “It is becoming one of the most useful tools to coordinate a variety of attacks and, traditionally, governments will prioritize eliminating risks like that.”

Doomed by Disinformation?

In this week’s informal ECT News poll, we asked readers how concerned they were about online disinformation during the U.S. presidential election cycle. Although we’re still polling and the final results aren’t yet in, a whopping 58 percent of respondents so far said they were “very concerned,” and 15 percent were “somewhat concerned.” In contrast, 27 percent of those polled were “not at all concerned.”

There was no waffling among our roundtable panelists. They’re very worried.

“Disinformation is everywhere. It is a potent weapon and made all the more so because many people simply do not recognize it as such,” said DiDio.

“Too often the news media is guilty of promoting opinion instead of fact and in trying to be first instead of right,” she pointed out. “Early on in my career as a reporter, Ted Kavanau who was the news director at WNEW-TV in New York, had a sign posted as you entered the newsroom: ‘There are two sides to every story. How many sides did you get?'”

There are many forces seeding the mushrooming disinformation cloud, Enderle suggested.

“The proliferation of disinformation increasingly tied to foreign governments and fringe groups is greatly concerning as is the increased use of false statements of fact from political figures and national news organizations,” he said.

“This appears to be tearing much of the West apart. Yet fixes could destroy free speech. These unfortunate trends could eventually destroy much of the democratic governments that exist and at the heart of the efforts are our own social networks. I fear the repercussions will be far more dire than we currently realize,” Enderle added.

“The problem is larger than elections IMHO,” agreed Moyle.

“The election problem is especially vexing because it involves foreign nations and such interference can be construed as an act of war,” noted Pombriant.

“We need to come together globally to agree on standards for what is OK and what is out of bounds. … It probably involves a cyberwar treaty or addendum to the Geneva Conventions,” he suggested.

“So Andrey Krutskikh, a senior Kremlin advisor, bragged about the Russian disinformation capability in 2016,” Moyle pointed out.

“They will absolutely do this again. They have to in order to achieve the objective they wanted, as a negotiation instrument with the U.S.,” he continued.

“So get ready for that. More disinformation incoming for sure,” Moyle said.

“While there is probably no way to know definitively one way or the other, elections prior to the 2016 U.S. federal election were not perceived, or forensically proven, to have been compromised by disinformation on social media — disinformation being intentional inaccuracy while misinformation is unintentional — despite the fact that social media has been a factor in campaigning for at least the previous two federal elections,” Terrasi pointed out.

“So the question we have to pose to ourselves is, did social media platforms actually become a more fertile ground for disinformation since 2012, or did the agent provocateurs and partisan political operatives simply get more adept in abusing social media to proliferate disinformation?” he wondered.

“It takes time for any actor to become versed in a new medium, and it could be that political actors are just acclimating to social media just as it took a while for them to fully leverage television,” Terrasi suggested.

“Political speech is one of the rare forms of First Amendment speech that is truly unlimited, so the government can’t really regulate what is said. Concurrently, social media has no incentive to ban all political speech from their platforms — even if they ban paid political ads, as some platforms have to date,” he added.

“Bearing all of that in mind, the only viable remedy for the manipulation of information intended for the political forum is tighter regulation on political spending, which is not something the federal government has pursued very far lately. Any change on this front will have to come from a bipartisan groundswell of popular support,” Terrasi maintained.

What to Do?

As grave as the problem may be, there are ways to combat the tsunami of disinformation, our panelists maintained.

“The problem, and it is serious, can be solved through certification of users, breaking up the vendors, and demanding transparency,” insisted Pombriant.

“This is an ideal use of a behavioral AI looking for data trends and red flagging them for mitigation, or automatically mitigating with a defined escalation path to remediate any mistakes,” suggested Enderle.

The best solution could be a more basic one, however. To reduce the effectiveness of disinformation campaigns, we need an increase in critical thinking skills across the board,” said Moyle.

“Many people aren’t trained well in critical thinking skills. They literally are unable to tell a biased or untrustworthy source from a reliable one,” he pointed out.

“Fixing this requires building up those skills — which is challenging to do. Long term, this issue will resolve itself. Young people now learn to tell the difference between news and spurious crap early as a survival skill,” Moyle noted.

“We likely should aggressively teach both confirmation bias and argumentative theory at a young age so our race learns to self-mitigate. We have found the problem and it truly is us,” Enderle added.

“The only sure defense is equipping everyone to serve as their own best advocate and critically evaluate all the information presented to them — and the motives behind its presentation. It is an arduous, unglamorous task, but it is the only one that promises a durable solution,” said Terrasi.

“Everyone needs to check and vet their sources of information and not simply jump to conclusions and retweet or share so-called ‘facts’ before they are certain that it is factual and correct information,” urged DiDio.

“Think for yourself and question everything! That’s a good start,” she said.

“In the digital age, information and disinformation is literally no further than our fingertips. Unfortunately, many people tend to consume information with less thought then they would give to what flavor they want in their morning beverage,” DiDio remarked.

“We as individuals and collectively as organizations — news, vendors etc. — have to demand critical thinking and apply standards and regulations for noncompliance,” she maintained.

Once disinformation hits the Internet, it’s very difficult to take down, DiDio observed.

“So there must be consequences. Current laws have many loopholes, and we as a society must work to close those loopholes — and we must also enact new legislation that keeps pace with and adequately delivers punishment that fits the crime,” she argued.

The Institutions That Sustain Us

One possible approach to stopping the madness could be to shore up the institutions that have served our society well when other crises have threatened the social fabric.

“The threat posed by disinformation is certainly dire, but I think it is early to sound the death knell for liberal democracies,” Terrasi said.

“I think some of this pessimism owes to the admittedly difficult nature of education-based campaigns, because all it takes is a large enough segment of uneducated or easily misled voters to swing an election — another case of the chain being only as strong as the weakest link,” he pointed out.

“I think that this effort can be bolstered by restoring integrity and vigor in our civil institutions,” Terrasi suggested.

“I know that that is a somewhat unpopular opinion at the moment, but institutions have historically been arbiters of contentious but complex subjects that make their outcomes felt on society at large,” he continued.

“I don’t think having expert bodies weighing in on complicated issues is a bad thing,” Terrasi added.

“What I will grant is that many institutions have been co-opted by narrow powerful interests, and that has to be addressed. I can accept if we need to clean house in some institutions, but I still think we need functioning ones to anchor public discourse in facts,” he emphasized. “It requires a compromise in which institutions admit their failings, and the public admits that ordinary people usually don’t have better answers to the intricacies of policy making than experts do.”