Global sales of electric vehicles in 2020 surged despite a drop in overall sales of passenger cars, a market research firm reported Monday.

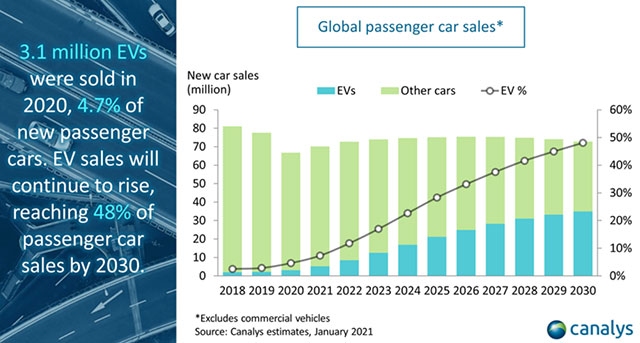

Sales of EVs jumped 39 percent globally, reaching 3.1 million units, while sales of passenger vehicles fell 14 percent, Canalys reported.

It added that electric vehicles represented almost five percent of all new car sales in 2020.

Canalys chief analyst for automotive Chris Jones explained that Europe was a prime driver of EV sales last year, with the vehicles garnering 11.5 percent of new car sales in the region.

“Europe has shown other markets what is possible when all parts of the puzzle are in place: emissions-based policies with penalties, internal combustion engine vehicle ban target years set, customer incentives, a broad and expanding charging infrastructure, much improved choice of EVs, good EV supply, customer awareness and, ultimately, customer demand,” he told TechNewsWorld.

Overall, he noted, 83 percent of all EVs sold in 2020 were sold in either Europe (42 percent) or China (41 percent).

Big Stick Incentives

New tougher emission standards played a role in European EV sales, too, added Sam Abuelsamid, the principal analyst for e-mobility at Guidehouse Insights, a market intelligence company in Detroit.

“Auto makers knew the new standards were coming in 2020, so in 2019 a number of manufacturers ended up holding back their available inventory because they knew they were going to have meet this more stringent target,” he told TechNewsWorld.

“There are some pretty hefty fines for manufacturers that miss that target,” he explained.

“So there was a pent up demand and the introduction of more new models,” he said. “That drove up sales in the European market.”

In a similar vein, he noted, more stringent regulations in China pushed up sales there, as well.

Additionally, a large number of EV buyers were in an industry that was able to skirt some of the worse economic impact of the global pandemic. “There seems to be a good overlap between EV purchasers and technology workers,” observed Ian Riches, vice president for the automotive practice at Strategy Analytics, a global research, advisory and analytics firm.

“Technology workers, as a group, found it easier to transition to home working, and thus had their incomes — and thus purchasing power — less hit by COVID,” he told TechNewsWorld.

Flat Growth in US

Meanwhile, in the United States, EVs represented just 2.4 percent of new car sales, Canalys reported, although sales did edge up by four percent over 2019.

“There is still no credible competitor to Tesla, and the demand is just not there in much of the country,” Jones said.

“That’s not helped by the lack of EV choice, particularly in the two hugely popular vehicle segments of SUVs and pickup trucks — which are on their way,” he continued.

Abuelsamid noted that as a new series of EVs are launched into the U.S. market this year and next, there will be a broader range of products to choose from at various price points. “That’s why I think we’ll start to see some acceleration of EV sales in the U.S. going into 2022 and beyond,” he said.

Jones maintained that the U.S. would benefit from stronger federal policies to encourage or force auto makers to launch more EVs.

“Our fuel economy standards are easier to achieve than the rest of the world,” Kevin Riddell, an analyst with LMC Automotive, an auto market research firm in Detroit, told TechNewsWorld

“The price of making the batteries and electric motors has come down, but it’s still expensive to sell EVs at higher volumes,” he said. “Subsidies are still needed.”

“Essentially,” Gartner automotive analyst Pedro Pacheco told TechNewsWorld, “the U.S. doesn’t have legislation that generates strong a strong EV sales push as in China and the EU.”

Automakers Change Their Tune

Some other factors are working against EV sales taking off in the U.S.

“Range anxiety is also still an issue putting many U.S. consumers off making the switch,” Jones observed.

“Fuel prices have also stayed relatively low so there’s less incentive for consumers to shift over to electric vehicles,” added Abuelsamid, “When gas is $2 or less, the economic case for EVs to the average consumer is harder to make.”

Also, while automakers are now onboard with EVs, that hasn’t always been the case. “Automakers slowed the pace of adoption and normalization of electric vehicles in the U.S.,” maintained Eric Yaverbaum, CEO of Ericho Communications,a public relations firm in New York City.

“These automakers deliberately undermined climate science and the negative environmental impacts of gas vehicle emissions in an effort to protect their bottom lines,” he told TechNewsWorld.

“This disinformation campaign was clearly successful, as last year only three percent of all vehicles sold in the U.S. were EVs,” he said.

“It’s clear now that U.S. automakers are changing course on this as consumer demand and all-electric competitors gain ground in the market,” he added.

Continued Rapid Growth

Canalys predicted EV sales will continue to grow throughout the decade, with EVs representing 48 percent of all new cars sold in 2030.

“Rapid growth will continue as more electric vehicles launch and governments set and maintain policies to stimulate EV production and sales,” Canalys Vice President Sandy Fitzpatrick said in a statement.

“Reducing ‘range anxiety’ with increases in performance and charging infrastructure will be vital to entice more buyers,” she continued.

“The automotive industry is currently facing crippling semiconductor shortages,” she added, “so managing future supply chains and production systems to cope with the growth will be make or break for any electric vehicle strategies.”

Abuelsamid explained that EVs rely more on electronics than internal combustion vehicles do. “They’re more software driven,” he said. “If there are disruptions in the supply of processors, memory or the chips used in the power electronics, that could pose a problem for EV sales.”

“The current supply issues with chips are expected to be a temporary disruption,” he noted. “By midyear or the third quarter, that will be resolved.”

“It’s an issue caused by the pandemic,” he continued. “Early last year, automakers cut orders for parts because they thought they’d be making fewer cars. Meanwhile, demand for computers skyrocketed. So the chip makers shifted their production to make chips for computers.”

“But demand for vehicles recovered faster than expected and automakers used up their inventories,” he added. “It’s going to take a while for the chip makers to get production in line with demand.”